- Home

- Murzban Shroff

Breathless in Bombay Page 3

Breathless in Bombay Read online

Page 3

“Alas, no, Mataprasad,” the mukkadam said. “Not this time. My friend says there are orders from the top. These builders have great influence. They have to get their buildings up in time. I am afraid we will have to bear up.”

“Arrey, what bear up, mukkadam? It is easy for you to say. You don’t have to face customers. You don’t have to face their anger. You just sit on that arse of yours, turning the water on and off the whole day—that’s all you do anyway.”

“Why are we keeping him if he can’t do his job? If he can’t even get us our quota of water?”

“Enough, brothers,” Mataprasad said. “There’s no need to vent your anger on the poor mukkadam. If we can’t get water from the municipality, we will buy it. We will call for a tanker daily.”

“How will that be possible, Mataprasad?” a dhobi called Roshan Lal quipped. “The tanker pipes are not long enough to go through the basti and reach the rinsing tanks. Besides, by parking on the main road the tanker will create a traffic jam, and we will have to face the wrath of the traffic police.”

“I wonder why God has given you a head, Roshan Lal, if you can’t use it,” Mataprasad said. “So what if the pipes don’t reach? We shall form a human chain and carry it in buckets. We can get the women to help, which will be good for them, because it will leave them less time for gossip. As for traffic jams, don’t worry about that. The mukkadam will take care of any cops that come by.” He looked at the mukkadam, who nodded promptly.

“Yes, but the cost for the tanker will have to be shared,” Ram Manohar said hurriedly. “We can’t afford to pay from the dhobi fund. Not until we get some more funds in.”

“But that will mean hardly any profit. What we are going to make God only knows! How are we going to feed our families? How will we survive?” groaned a voice in the congregation.

“Do not despair, brothers,” Mataprasad said, trying to sound composed and cheerful. “The cut cannot last forever. If it does, we can always protest. We can take it up with the municipality and with the corporator. We can go all the way to Mantralaya, if necessary. Remember what our brother dhobis in Patna did? They refused to wash the clothes of the ministers when they were eyeing their ghat to build a bazaar in its place.”

“Yes, but today who cares if we refuse to wash clothes, Mataprasad? They will laugh at us, replace us with washing machines. This is Mumbai, not Patna.”

“There is nothing left, Mataprasad—nothing in this business. Why do you fool yourself? Why don’t you admit it is all over? The dhobis will never enjoy the status they once did.”

Heads turned. Standing in the aisle, at the far end of the gathering, was Shyam Pardesi, one of the few men who wouldn’t be affected by the water cut simply because he wasn’t a dhobi. Pardesi worked as a union leader in a packaging factory where the workers had been on strike, agitating for higher bonuses. The factory management had refused to give in to their demands, and Pardesi had been out of work for a long time.

“How come you are up so early, Pardesi? Was the liquor you had last night too mild or what?” Mataprasad said. There was an itching below his mustache, a tingling that did not augur well.

“You can say what you want, Mataprasad, but there are times when sitting and drinking at an adda has its advantages. That is why I am here—to share with you some excellent news.”

The dhobis craned their necks and shifted. For a moment they thought that perhaps Pardesi was drunk, that he was reeling under some liquid daydreams or his unemployment had affected his mind.

“You may come here and say what you wish, Pardesi. You know ours is an open meeting,” Kashinath Chaudhary said stiffly, concealing his disapproval of the union leader.

Pardesi came up. He was a slim, pock-faced man, in his early thirties. He had narrow, crinkly eyes and hair that curled over his ears and neck. Unlike the rest of the dhobis, who wore kurtas and dhotis, Pardesi wore modern clothes: a printed shirt, jeans, and a belt.

“Friends,” he said, clearing his throat, “I don’t need to remind you that things are not what they used to be. There was a time when we were among the foremost communities of Mumbai, when people couldn’t imagine life without us, because the work we did was held in great esteem. In fact, there was a time when a whole lake was named after us—Dhobi Talao, as you know, was where we washed the uniforms of the British soldiers—and the ghats were given to us as our own proud places of work, as high points of trust and respect. Today, unfortunately, things have changed. It is the day of machines and gadgets. In our factory too many workers have lost their jobs, and who cares, really, whether the workers live or die? Now, you might say that I do not belong to your trade, that I am not a dhobi, but don’t forget I am the son of one. My father, Namdeo Pardesi, raised me and my four sisters from the money he made as a dhobi, which is why I feel for the trade and for all of you.”

“We don’t have time for your bhashan, Pardesi. Leave that for your union meetings. Let’s hear what you have to say. We have deliveries to make.” The voice came from the center of the crowd, and it made the dhobis laugh. Mataprasad smiled, too, glad for the break in tension.

“Okay, friends, since you can’t wait, hear me carefully. There is a chance for each of us to make good money, more than what we would ever make in our lifetimes. You have seen what is happening to the city today, and particularly to our area: construction everywhere—old buildings being broken down and new buildings coming up. A lot of this is under the city’s slum removal plan, which allows builders to remove slums and put the slum dwellers up in new flats of 225 square feet each. In exchange for housing the slum dwellers free of charge, the builders get space to build tall buildings, thirty to forty stories high, which they can sell at a great profit.”

“How does this concern us, Pardesi?” Mataprasad said. He was frowning now and knew not why but he felt a premonition, not on his upper lip but in his stomach and heart.

“It concerns us greatly, Mataprasad, for yesterday when I was drinking at Narang’s adda, I met two men who are working for a builder, the same who built those towers there,” Pardesi said, pointing to the two tall buildings behind the ghat.

The dhobis turned to stare at the skyscrapers. To Mataprasad’s eyes there appeared something insolent about the structures: the way they rose in piercing defiance to the calm azure sky. He knew not why, but he felt the buildings were alive, their concrete embodied with some strange spirit that was waiting to swoop down on the inhabitants of the ghat and crush them.

“The builder’s men were quite friendly and after a few drinks they spoke freely,” Pardesi said. “They suggested they first get us registered as a slum. Although the ghat is a green zone protected against development, it can be de-reserved and brought under the slum removal plan. These things are easy to fix. All it takes is our understanding and our signatures. If we agree and give this place to the builder, within two years we can each own a house of 225 square feet. Going by the rate in this area, this comes to over rupees twenty lakhs. When I heard this, I was stunned. I thought why are we wasting our time in a dead trade? Why are we slaving and worrying about a future that seems bleak? Why are we not thinking like men of today and taking an opportunity? I say this is a God-given opportunity and it has come to us on a platter. So I said to the men I will speak to you and let them know. Of course, I will take my commission.” Smiling, Pardesi turned to the panchayat. Their faces would tell him how his suggestion had been received.

“Have you gone mad, Pardesi? Has your drinking affected your senses? You are asking us to sell our ghat, our land, to betray our trade after all these years?” Mataprasad rose, a dark, steely-eyed colossus. He was followed by Ram Manohar and Kashinath Chaudhary. They rose and stood with grave expressions, legs astride, hands folded over their dhotis.

“What trade, Mataprasad?” Pardesi asked. “Shrinking kheps, water cuts, rising prices . . . how long will you struggle? How long will you endure? How long do you think your ghat will support you? Look at it! It is only a mount

ain of rock. Does it care whether you have work? Does it come to your rescue when the municipality increases your taxes or when it cuts your water? But now your ghat is trying to tell you something—that there is a value to it, if only you see it. It is ready to sell itself, to keep you afloat, Mataprasad. You and all these people here, who depend on you.”

“So, for that you will have our ghat called a slum. You will reduce our trade to something negotiable, huh, Pardesi? Tell me, how much commission are you getting for this? How much are the builder’s men paying you? And how did you even think that we would support you in this vile scheme?”

“Wait, Mataprasad; maybe we are being hasty. Pardesi has a point. Rupees twenty lakhs is a lot of money. If we invest it wisely, it can take care of our old age. It can buy us land in our village and pay for our sons’ educations and our daughters’ marriages.” The voice belonged to Jodimal Vikas, a mild, elderly dhobi with a bony face and damp gray eyes. Mataprasad knew that Jodimal Vikas was finding it tough to get grooms for his two thirty-plus daughters. It was the usual story—the higher the age, the greater the dowry.

“What are you saying, Jodimal bhai? I know times are tough, but that is when we must be strong. We can’t go selling the ghat, which has been like a parent to us.” Mataprasad’s voice was kindly, but a sense of despair had seeped in. Thankfully, it was evident only to his ears.

Sensing an advantage, Pardesi interjected. In an aggrieved voice he said, “I don’t know, brothers, but when I spoke to the builder’s men I was only thinking of your welfare. How was I to know I would hurt your feelings? How was I to know I’d invite such allegations and insults onto myself? Please forgive me if I have said too much or have spoken out of line.” He began to walk away when a shrill, agitated voice rose.

“Wait, Shyam bhai, please don’t go! We want to know more. Will the builder give us transit accommodation while the building is coming up? Will he buy back the flats once the building is ready? Will there be an agreement in writing?” Then, addressing the dhobis, the voice said, “I say, brothers, we give Shyam Pardesi a chance to share what he knows. He has brought Lakshmi to our door, and we are shooing her away. Why do that to the Goddess of Wealth? Rupees twenty lakhs is no small sum. We owe this not just to ourselves but to our children, too. How will we face them knowing that we had this opportunity and let it pass?” Mataprasad clenched his fists. His eyes narrowed as they fell on Daman—a new, inspired Daman, with his hands on his hips.

THE TRAIN HISSED and cut its speed. Beyond the tracks, small buildings whizzed past, buildings with shops below and grilled balconies above, and clothes hanging on crowded lines, blocking out the entry of air. Along the tracks, a woman washed clothes. Her sari was rolled up; her knees were bare and gleaming. Next to her, a girl bathed. She washed herself moodily, as if the whole ritual was a chore, a silly self-imposed ordeal. They both failed to look at the train, to take heed of its thundering proximity. Mataprasad saw them clearly, as he did the half-filled bucket before them.

MANY OF THE YOUNGER DHOBIS agreed with Pardesi. They felt why get sentimental about a hill? It had earned for them and was doing so now, giving them a benefit plan for keeps. In their minds, they dreamt of businesses like phone booths, photocopiers, and stationery shops, preferably outside a girls’ college, where fresh-faced girls would flock to spend their allowances. They saw themselves with luxuries like motorcycles, cell phones, and movie tickets—all that had been denied them this far. Ram Manohar and Kashinath Chaudhary tried to maintain order, but it was impossible to curtail the babble of excitement, the doubts, queries, and dreams, which were being excavated and expressed freely.

Mataprasad tried to protest. Through clenched teeth, he tried to tell them what he knew—of the dismal conditions in the transit camps: no sanitation, no power, rationed water, the location some God-forsaken place outside the city where there’d be no opportunities for work and where they could easily be forgotten. He tried to tell them that he had been through this kind of thing, in his childhood, in his village, when his people were asked to move out and make way for a dam. They, too, had believed those promises of more land, of greener fields and higher yields, and then received nothing but the unchanging squalor of a transit camp. He tried to tell them that home was home and to abandon it for greener pastures was like cutting off your nose to spite your face—the consequences were indeed terrible. He tried to tell them that this was the mistake that had brought him to Bombay, in his teens, to earn and save, so that he could get his family out of the transit camp. But he had failed to do so. His younger brothers—the twins—had died, one from dengue, the other from typhoid. Distraught and depressed, his mother had lost her mind and wandered off into oblivion. His father had taken to drinking and died two years later, out of some kind of searing shame because he wasn’t able to hold his family together. Mataprasad had realized the hard and bitter way that there was no point going back to the country; his life there was over. He tried to tell the dhobis that that’s how they came to be his extended family; that’s why he had tried to build them a village within a city, a home with traditions not unlike those of the one they had left behind. Had he not succeeded? Had he not built a community that was united and bonded by traditions? And weren’t their homes exactly like those in the village: without doors, without locks, open to all who wished to enter? And now they were ready to trade it all away. For rupees twenty lakhs, which would disappear as soon as it came, giving rise to new habits and new temptations.

He could see the dhobis did not wish to hear him. It was Shyam Pardesi they wanted to follow. The union leader had spoken his way into a new job. The era of the ghat panchayat was over. The city had crushed the village, concrete had triumphed over mud, man had gained control over nature, and, like the ill-fated ghat, the panchayat had no option but to dissolve itself into the earth, to melt and mesh with the ways of the city.

THE TRAIN STOPPED. Mataprasad saw he’d arrived. He swung his khep over his shoulder and stepped out onto the platform. A bootpolishwalla struck his brush noisily against a foot stand. He did this many times over, an invitation for passersby to get their shoes polished. But, alas, Mataprasad wore only chappals. He had never known the comfort of shoes—too confining like the city. A gypsy woman in bedraggled clothes helped herself to water from a fountain. She collected the gushing water in a rusted old Dalda can. At the food stall near the entrance, some people stood, sipping chai, eating vadas, while near the ticket counter children begged and played intermittently. One of the beggar girls, a dark, sweet-faced ten-year-old, with hair falling over her forehead, came up to Mataprasad, and, rubbing her flat stomach, said, “Hungry, no?” And Mataprasad fished out a coin and, ruffling her hair, said, “Who is not, child? These days, who is not?”

Adjusting his khep into a convenient carry position, Mataprasad strode past a weighing machine. Its red circling disk and flashing lights invited him to weigh himself, to take stock of his burden. But ah, there’d be no correct measure for that, he thought. Nothing that would add up.

Walking out into the blinding sun, Mataprasad took the bazaar lane leading to the main road, which in turn would lead him home.

The bazaar was emptying out. The vendors were packing up for lunch. They flung damp sheets of jute over the baskets of fruits and vegetables to keep them fresh. Some of the vendors called out their closing prices, and some women stopped to consider them.

Halfway down the bazaar, Mataprasad came upon a fisherwoman. Her basket was heaped with sardines, and on top of the sardines was the most enormous kingfish he had ever seen. Its silver body, gleaming in the sun, seemed to be alive, breathing, and staring straight at Mataprasad.

His eyes narrowed. His mouth turned moist. Pointing to it, he asked the fisherwoman, “How much?”

“One hundred and twenty rupees,” she said. “But to you I will give for one hundred,” she added coyly.

“Why, sister?” Mataprasad said with a grin. “Do I look like your brother or what?”

“You want it or not?” said the woman with a scowl, a flush of red appearing on her face.

Just then Mataprasad heard a sound—a meow sound, once, twice. He turned. A bunch of stray cats were eyeing the fish. Their gray faces were locked in a snarl; their paws were taut and extended. They strained and they hissed, but they would not approach the basket. Mataprasad made as if to chase them, but the fisherwoman said, “Don’t worry about them. You just say whether you want the fish or not.”

“Aren’t you worried that they will get at the fish?” Mataprasad asked curiously. “Then you will make a loss.”

“No,” she said. “You see this?” She shifted the basket slightly, to reveal small pieces of ginger cut and arranged in a circle. “This is what keeps them away. They can’t bear the smell. No matter how hungry they are, or how tempted they get.”

Mataprasad scratched his jaw and gave a low laugh. “You mean that’s all it takes to protect your fish, a smell that the cats can’t endure? Why, you are cleverer than I thought.”

The fisherwoman blushed. “Go on now, saying nice things like that to me. I am not going to give it to you for less than one hundred. I am telling you that now.”

Mataprasad thought for a while. It seemed a shame to bargain with one who had learned the tricks of guarding her business, of protecting her trade against greedy intruders. It was something Lacchman Dubey hadn’t learned after all his hours of puja. Nor he, after all his sacrifices to build a village within a city. Nor the panchayat members with whom he had sat in council for years, thinking their position impregnable. This art of concealed self-defense: it was not something Mataprasad had learned, but which he could easily admire.

“Tell you what,” he said to the fisherwoman, who was looking at him hopefully. “I will take it for one hundred and twenty. But you cut it, clean it, and put it in a bag for me. Then we are both happy.”

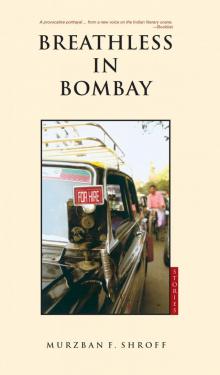

Breathless in Bombay

Breathless in Bombay