- Home

- Murzban Shroff

Breathless in Bombay Page 6

Breathless in Bombay Read online

Page 6

Vicki thought she’d be the good thing in his life. She dreamt that she’d give him back his lost childhood, and she allowed him to curl up night after night in her arms, in the folds of her body, all the way down to the burning epicenter of her soul. Where he’d been abused, places where he’d been hurt and damaged, she filled with love and devotion, a tenderness she never knew she possessed. She’d hold him, stroke him, shower him from head to toe with sweet, moist kisses, as if plucking and drawing the poison out, as if taking it in herself.

Her tenderness would give way to a torrid lovemaking, mostly silent, in the dark, and she’d note the rise of a slow, clutching panda anxious to prove himself. Not ready to disillusion this victim-child of an abusive father, she’d moan and groan away. She hated herself for doing this, for being this wily, thrashing woman, but if it served to enhance Nandkumar’s confidence, if it made him feel as good as the next man, she was game. When they were like this, she’d dream of old boyfriends, old lovers, men she’d been with for a night, or for a month, boys at her college, and some later, who were there only to deliver, only to quench, and who made her feel empty and cheap thereafter. And she knew then that no matter what his failings were, in bed and out of it, it was this child she wanted, this responsibility she craved.

She thought she’d be his savior, his destiny. She thought he’d see it this way, too, and she allowed herself to dream fervently, to stroke his lush black head and his soft furry eyebrows, and his drooping vodka eyes, averted, uncertain whether he’d delivered at all, and she would sigh and bestow what she felt were kisses of lasting assurance. She never wanted him to know the truth. She never wanted him to feel he was a lesser man. She diminished herself on the altar of his love, gave up those womanly notions of fulfillment and reciprocal warmth. And she readied herself for a lifetime of sacrifice—whatever it took to keep the man intact.

While he’d sleep and snore lightly, she’d dream that she’d bring him luck; his work would get noticed and begin to sell. To do that, she took copies of his work, scanning and printing them out in large-size formats at her own expense, and these she showed to owners of art galleries who she knew were open to new artists. She didn’t tell him, but she got these contacts from her boss, the Bollywood producer who was a big enough name to open doors, to call and invoke, if nothing else, some curiosity on her behalf.

Wherever she went, she got the same response: he is good, talented, excellent control, but people don’t want to see angst on their walls, they don’t want to face death and destruction; they want, well, wall art, or art that would enthrall and intrigue, or art that was solid and definitive, or art that was surreal and abstract. There was so much more he could do in figurative drawing, making it more defined and less grim.

One of the agents, a kindly old gentleman in whom she managed to inspire a paternal emotion, went to the extent of suggesting themes. Could he do a series on the heritage trades of Bombay: a maalishwalla by the beach, a victoriawalla under a streetlight, a dhobi buckling under his load—something to suggest his heavy debt? Now that would work. He’d be glad to represent that kind of work.

When she told Nandkumar about the agent’s suggestion, he said, “Tell him to take his ideas to painters who are hard up for ideas.” He said he was better off where he was. Better off in his own bed, under his own ceiling, smoking dope with his father’s money, and dreaming up rebellions in his mind, rebellions that would never happen. She knew that as well as he did.

She kept trying, and he kept refusing, kept avoiding opportunities, as if the very idea of responding to them would imply a selling out, a beginning of the corruption process. She understood that there was an inborn fear of rejection, of being told he wasn’t there, he was too indulgent, too dark and depressing. She understood that he couldn’t operate without the fear of a cigarette over him. Its light and its threat.

Slowly, a change came over her. She found that she preferred staying late at work. The whole idea of returning home and finding him soaked in vodka or in depression filled her with a strange dread. Yet she loved and wanted him. Yet she kissed him warmly once she returned. Yet she melted when she saw that he hadn’t eaten without her and he offered to heat her dinner despite his inebriated state. Looking at moments of closeness for inspiration, she tried to talk him into working, into pulling himself up. She tried to remind him it wouldn’t be a compromise listening to what the agents were saying; it would be an investment for the future, their future, so to speak. She’d look at him with anxious eyes, wondering whether he thought of that as well.

But to all her pleas his defense was: “I can’t sell out. I can’t go and kiss ass, do things I don’t believe in. They have to take me for what I am,” and then slowly he’d add: “So must you, if you believe in me, if you believe in the work, and don’t want to give up on us, all that we stand for.”

And when he’d say things like that, when he’d transfer the onus onto her, a wild fear would spring to her eyes. Was this a threat? Or a challenge? She couldn’t take any more responsibility than what she had already. Not because she didn’t want to, but because it didn’t seem to be working; it didn’t seem to be getting them anywhere—to the possibility of a dream taking shape.

A few days before Diwali she saw him brood over a letter he had received. He read it again and again, pacing up and down the tiny passage along the living room, frowning, and smoking one cigarette after another.

“It’s from the landlord,” he said after some time. “It’s an offer to convert this rented house into an ownership one. One hundred months’ rent and it can become mine for life!”

She flinched at “mine” but chose to let it pass. “So what’s the problem?” she said. “It sounds like a perfectly good proposition. Considering what an ownership flat would cost in this area, you stand to gain.”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t know whether Dad will agree to pay. I suppose I had better go and see him. Do you mind? I will be gone a few days.”

She was glad for the break, glad to see him off the next day, in an unreserved compartment of a train starting from Dadar Station. This was another of his quirks: he liked to travel with the masses; he liked the sweat, the suffocation, the rubbing of shoulders with the proletariat. He said he was as public as they were, the unfortunate product of an unfortunate birth, and that he did not wish to be any more removed from reality than what he already was.

With him gone, she’d come home early, play her CDs, fix herself a bubble bath, soak in it, and give herself to a world of creams, lotions, and other feminine cares that she had given up. She’d leaf through women’s magazines, reading with interest the personal sagas, the personal advice columns, and the zodiac predictions that told her what the future held. Then one day she decided to invite her relatives over for dinner, her two chachus and two chachis whom she hadn’t seen since the time she met Nandkumar. She thought this was a good time to tell them of her live-in arrangement with this sweet and not-so-steady boy from a not-so-great family. She spared them the details of his childhood but spelled out those of her own happiness at great length, requesting their blessings, and although they were a little hurt, they agreed to meet Nandkumar.

“Oh, but you can meet him right now,” she said eagerly. “At least a part of him.” She proudly brought out his paintings, thinking this was the best way to introduce him.

She was in the midst of showing them his work, explaining its deeper motivations and the details they would have missed, when there was a click at the door and he came in looking tired and disheveled. His hair was tossed, his cheeks were flushed, his neck was dark with perspiration, and his eyes had a vitreous look, a false alertness to suggest that some vodka had been consumed. “Ah,” he said. “And what is this? A party in my absence! Something I should know about?” She flinched at his tone, for light as it was, it carried a hint of accusation. Her heart sank and a slight rage began in her. Why did he have to come in right now looking like this? Could he not have phoned her,

warned her? He was so much more attractive in his absence.

“Oh, Nandu,” she said, trying to sound pleasantly surprised. “This is my Ajay Chachu and my Vinay Chachu, and my chachis, Anjali and Gauri—you’ve heard me speak of them.”

“Ah, yes!” he said coldly. “But I didn’t know they were connoisseurs of art. I didn’t know you were going to be holding a private exhibition while I was away. You might have at least asked me? Unless, of course, the idea was different—to wait till I was gone.”

“Honey . . . it’s not what you think. They asked what you do. I thought this was the best way.”

“Best for whom? And with whose permission? Perhaps you could clarify, Vicks.”

“Nandu, please, why don’t you go in and freshen up? There is some nice food ordered. Wash up and join us. They are dying to know you, to talk to you.”

“Wash up and join us,” he chided. “Honey, I am shocked. What have you been telling your people: how obedient I am, how I need to get my instructions from you, or I fail to make it through the day effectively? Oh, please, we can do better than that, can’t we, Vicki?”

“Nandu, please!” she implored, making eyes at him, desperate eyes, despite her anger, which was welling up.

“Go on; I am listening. I expect to come home to a bit of rest, a bit of privacy, and what do I find? My paintings on display before people who don’t know a dot about art, who’ve probably never been to an exhibition in all their lives. Or have never stepped out of their homes to see what’s happening elsewhere in the country, how the other half lives.”

“Young man, you presume too much, and I don’t think I like your tone. We see how wrong our niece was when she said all those nice things about you.” This was her Vinay Chachu, firm, soft-spoken, almost like a father to her.

“I think he is drunk; I can get the smell. Maybe that’s why he is being so rude.” This was her Gauri Chachi, the observant one.

“I think, Vicki, you have made one big mistake. You will ruin your life if you settle with this mannerless fellow. Look at him, taking off at us like this. And for what? Just because we are seeing his paintings. Cha, who wants to see them now? All humbug they look like anyway.” This was her Anju Chachi, the tactless one, the unsparing summarizer of all things unspoken, and Vicki’s favorite.

Nandkumar dropped his bag, moved forward, and stood glowering at Anju Chachi. She met his gaze without flinching. He grabbed his paintings and leaned them against the wall. Then he said through clenched teeth, “Get out . . . all of you . . . and stay out. I don’t want to see any of you here again.”

“Arrey, don’t think you can insult us and get away with it. Our niece is not going to stay with you long if you are so badly behaved. What do you think? She comes from a good family. Not like you, you bloody hooligan.”

“Anju, please . . . let’s go. It was a mistake coming here. We can see that now, Vicki,” her Ajay Chachu said, turning to her. He got to his feet, and the others followed.

Vicki looked desperately from them to Nandkumar and to them again. She couldn’t believe this was happening to her. Her little world, which she had planned so carefully, was crumbling, and it was all his fault. But how was she to know that he’d be back? How was she to know he’d feel this way about his paintings? But didn’t they belong to her as well? Had she not taken them to heart, dreamt of their success, tried to give them a future? She found herself hating his paintings, hating his talent. His talent had created a wall between them. It had let her down before people whom she cared for. Oh, what greater humiliation than this? She felt a flood of tears build up, and she ran inside, while her relatives left and he slammed the door behind them.

For a long time she sat on the bed and cried, a stunned, brutalized pup, choked and horrified. She was sure that she had no family left; they wouldn’t respect her anymore. Oh, why had he done this? What purpose did it serve? She couldn’t even find the right words to reprimand him.

He came into the bedroom and without a word disappeared into the bathroom. When he came out showered and sweet smelling, he made a joint, lit it, and after the first drag said to her quietly, “Don’t touch my paintings again. Don’t ever make that mistake again, please.”

His eyes were cold, penetrating, and unavailable to her. It was as if they had shut her out. She nodded helplessly. There was a new fear lining her throat. It left her speechless. It hammered at her mind, opening it to dark clouds that warned of a deeper storm in future.

PARP. A SHARP HORN BEEPED in her ear. She shrank back. Oh, her concentration was wavering. She was crossing once more and needed to be careful. There was no signal here, no cops to control or to direct the flow. The traffic was coming from all sides, an unplanned anarchy, a free flow of metal, the city left alone to find its own method, its own discipline, which just wasn’t there. It happened because the cars were too many and the roads too few.

SHE TOOK THE NEXT FEW DAYS OFF, calling up work to say she was unwell. He stopped speaking to her, stopped cooking, too; not that it mattered, there was enough food left from what was ordered for her relatives. She didn’t feel like touching any of it; eventually it all had to be thrown away.

A brittle tension hung between them, a sadness that bewildered her. He would slip away early in the afternoon and go spend the day with his musician friends at the studio, where he’d smoke pot, drink vodka, and listen to the music of his youth. He’d return home late at night, wretchedly drunk. He’d crash noisily beside her, and within moments he’d be off, snoring heavily. While he’d sink into a sour sleep, she’d lie awake on her side, wondering how deep his poison was, how infectious its breath.

She didn’t have to wait long to find out. The phone call came while he was out and while she was just beginning to get a grip on herself. She’d started taking calls, coordinating a few things from home, and had promised her boss that she’d be back at work within the next day or two.

The caller announced himself as Major Singhal from the Maratha regiment, and he sounded very curt and very angry. He asked for Nandkumar, and when she informed him that he wasn’t there, he said with vehemence, “Well, madam, you just tell that young bastard that if I ever find him in Deolali again, I will give him the thrashing of his life, a thrashing he will never forget. I will make him pay for what he has done to his father. He will wish he were never born.”

“I don’t know what you are talking about, sir,” she said coldly. “If my knowledge serves me right, it is Nandu’s father who has a lot to account for, for what he has put Nandu through.”

“Young lady, I don’t know what your relationship with him is, but since you are around while he is not, I would infer that it is one of significance.” He paused. “I believe by your tone and confidence that you don’t know what has transpired, what happened when he came to Deolali. There was an argument, and he has left his father with a broken nose and two fractured ribs. And over what: just because the old man refused to give him some money, which he wanted for his house. And why should he? Isn’t it enough that he has given him an entire house in Bombay? Isn’t it enough that he sends him money every month? Which father would do that for a thirty-year-old son? Hah, if I had a boy like that, why, I’d leave him to fend for himself, a no-good wastrel of a fellow. And I’d break his face if he as much as raised his hand to me. I wish you’d see, madam, how much pain the old man is in, and yet he chooses not to make a complaint against his son. He didn’t even want to tell us, till we heard it from the old maali who had overheard the fight.”

Vicki felt sickened. Something churned in her gut. Yet she said, “Are you sure, sir? Are you sure of what you say? I don’t think Nandkumar would do something like that. He is not capable of it.”

There was a pause on the other side. “Young lady, you are either foolishly in love or just plain foolish. I don’t know you, but you had better wise up about him. That boy is a lunatic; take it from me. Who in his right mind would strike and injure his own father—and one so gentle, too?”

&nb

sp; “Is Mr. Chaurasia gentle?” Vicki asked in a low voice. She felt a faint tremor in her voice. The carpet, she felt, was slipping beneath her.

“Gentle? He wouldn’t hurt a fly. Of course, he wasn’t going to relent over the money for the house, but why should he? He is retired, living on his pension and his savings; he has himself to think of.” Suddenly the voice turned brusque and commanding. “Please tell Nandkumar from me, please tell him that we know what he has done, and that the next time there will be no warning. The army will do all it can to protect senior citizens. And we have our ways.”

After he had hung up, Vicki sat brooding a long time. Was everything about Nandkumar a lie? Everything, including the bit about the abuse? She knew now why he’d returned in such a foul mood, why he had been so furious to find her relatives there, and why he had insulted them. He had come home expecting to find consolation—to deliver stories about his father’s pettiness—and instead he had to make himself sociable. He couldn’t take that, not with the vodka, the fear, and the guilt raging through him. Vicki wondered how far back the lie stretched, how deep the pus was rooted. The gangrene had set in and it could infect her, drag her down. For the first time since she had met him, she thought of leaving. But she just thought about it, never did anything, just sat and thought in the dark, till the streetlights came on and lit up the windows and the plants cast dark, ominous shadows on the floor. She waited for him to come home—drunk, surly, and unsure—and then she told him about the call.

He denied it. “What Major? What injuries? That old bastard is shamming. It’s just his way to get pity, to make me look bad. He’d stoop to anything to get back at me.”

“But why would he get back at you at this advanced age?” she asked.

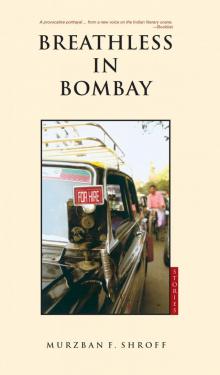

Breathless in Bombay

Breathless in Bombay