- Home

- Murzban Shroff

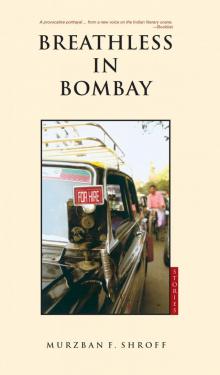

Breathless in Bombay Page 7

Breathless in Bombay Read online

Page 7

He scowled. “How would I know why? Did I know why he tortured me with that cigarette? He probably hates me because I was slow and he can’t bear it that I have overcome my problem and gotten over my fear of him.”

“The Major said he was gentle, he wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

“That fucking Major wasn’t there to see me grow up. He wasn’t there when the old man was not so old and I was so very young, face-to-face with that burning stick. That Major wasn’t there to see me get it—here, and here, and here.” Saying that, he slapped himself on his arms, hips, and thighs. Then he started jeering. “You seem to have believed the Major, haven’t you, Vicki? Oh yes, don’t you try and deny it. I know by your tone that you have believed him. And I thought I could trust you. You were the only one who knows everything, and yet you choose to disbelieve.” He sighed. “I guess it is too much to ask to expect total trust. Times like this show how wrong you can be. How misplaced your faith in the one you love.”

“It’s not like that,” she said. She didn’t know what to believe anymore. She was tired of him, of the dark, swamping chaos in his soul, which seemed to envelop her, draw her into a plunging gloom, an irreversible illness from which she could not fight her way out.

“Ah, yes, I remember now. My father was saying horrible things to me before I left. He kept coming up and sticking that hand of his in my face. I couldn’t bear it anymore. It reminded me of the abuse. Besides, I couldn’t take his selfishness. So I pushed him away, nothing hard, just a shove to get him off my back. Then I left. But I remember him falling, and when I offered to help, he shrugged me off. I told him that would be the last time I’d be seeing him. Perhaps that is why he made up this story. He doesn’t want to let go his hold on me.”

He looked at her. His eyes were calm. To her they appeared grayer than ever, a mixture of shades they were trying to conceal. It was dark and silent outside. Only the occasional roar of an auto rickshaw, or the sound of footsteps scrunching on the gravel outside.

“I’ll tell you what,” he said suddenly. “I bet it was no Major who called, but someone my father put up to it. I had told him about you, how we plan to get married and have kids. So if he could let us have this house, put up the money for it, we could seal our future. But did he listen? No! It didn’t matter, he said. Didn’t matter what I wanted to do, what became of us. Now tell me, would any father say that? Does he have any right to call himself a father after that?”

A shudder of excitement ran through Vicki. Marriage? Kids? Had he really said that? Did he mean it? She looked at him, his eyes craving her trust. But why would he tell his father about them, she thought, when he had not broached the subject with her?

She drew herself up. “Why must you depend on him?” she said. “Why can’t you raise the money yourself? Why can’t you do it with your work, your talent? Why can’t you be like the people you admire—the working class, who suffer indignities daily? Why must you be like one of those amir baap ka betas, one of those rich kids who get it all on a platter? Aren’t your actions in direct contradiction to what you believe? And aren’t you doing the same thing your father did to you? Aren’t you feeding off his old age, the way he fed off your childhood?” She stopped. Her poison was out, all that she had gathered in the last few months, all that she’d swallowed and left unsaid.

Nandkumar looked like a storm had hit him across the face. He clenched his fists and said, “You bitch, you fucking bitch, you are saying this, living under my roof and sponging off me?” He came and stood close to her, so close that she could smell his anger, his heat. She shut her eyes, raised her hands to her face, and waited for the blows to come. In a perverse sort of a way she wanted it to happen, for that would tell her if he’d beaten the old man as well. After some time she knew he was no longer there, for she heard the bedroom door slam shut.

That night they lay back-to-back, ruptured souls pretending to sleep, each grappling with a private hell, a raging inferno in their heads, each seeing the chasm between them widen, for they could no longer face each other, no longer share the same breath, the same rhapsody of body rhythms, rising and falling, rising and sinking, finding its own level, its own depth. They could no longer do that, for one wore the face of a liar and the other the face of loathsome disbelief.

He began to show a strange side thereafter, especially when they’d meet with her friends. He’d wait for an evening to settle in, for conversation to flow—a book, a movie, or a play to be discussed—then he’d look for an opening, a comment borne of ignorance, or a loose comment somewhere, and he’d move in with a cold gray smile, and end up going for his victim, going hammer and tongs with the full flesh-and-blood faculties of his mind, and he’d enjoy seeing his victim squirm and lose his cool, and he’d come away feeling nice and triumphant, nice and bloated, a sense of achievement plastered all over his hot, drunken face.

Many were the evenings that ended like this, and many were the times she’d lead him away, a hazy, vodka-ridden figure unable to hold himself up. It appeared, too, that he enjoyed the idea of a storm, of a slow, seeping anarchy that whipped itself into something big and left the evening in tatters, and he made no effort to understand the people he hurt, or what their relationship with her was, or just her and her feelings, and there was no inclination to apologize later, to mend bridges burnt and damaged. In fact, he seemed to flaunt some kind of bravado, some kind of bluster not human at all, and he seemed to blame her for knowing such kinds of people. People, who, he said, they shouldn’t waste their time on.

After some time her friends stopped inviting them. They decided she’d made her own choice, one that did not suit them, one that diminished her charm and wiped out the memories they’d shared. Besides, they had their own boyfriends and husbands to think of, bruised boyfriends and furious husbands, who did not forgive easily.

Her Anju Chachi and Gauri Chachi would call regularly on her cell phone and plead for her to leave him. What was her problem? Why was she staying? They’d find her a boy, a suitable boy from a good family, pleasant manners, pleasant looks, the kind who’d fit in with them, the kind who knew how to respect elders and would therefore respect her. And yet she could not leave, for she knew not what she’d be leaving: a dark genius or a poisoned child, a genius cheated out of opportunity or a child cheated out of love. There were two beings that crept into her bed every night, and she wondered who would win eventually, who would prevail and hold sway.

When she was on the phone with her aunts, there’d be a faint ironic smile playing on his lips, as if to say he pitied her. Casually she’d try to move out of range, and yet he’d be watching and smiling, his eyes riveted in a gloating sort of a way. When he did that, she’d feel a dark, hot unease, a sense of violation, a sense of losing her privacy, her control, and the house that had appeared so cozy earlier would suddenly become small and suffocating—a maximum-insecurity prison from which there was no escape.

She’d call her friends, not from home but from the office, and twitter how busy she was, how she missed them, how they must catch up once her film was done. She’d ask about their boyfriends, their husbands, and their work, and they’d answer sorrowfully, with a sense of awareness that she was flogging a dead horse, she was trying to keep alive something that had died one vodka-flushed evening.

They knew, and she knew, and so did her aunts and her uncles, and yet she battled this feeling that she must leave. That she must close the door and move on.

He threw her out one night after a fight. There was a mahurat of the film she’d been working on, a commercial film, a potboiler, with great drama, glitz, razzmatazz, filmy style, the kind of stuff he detested—which, he said, polluted the mind.

There was always excitement about such an occasion, and she had taken care to dress up. He had watched from the corner of his eye: she shading her eyes, patting her churidaar, rolling up her hair in a silken bun before the mirror. He watched her going through her box of jewelry—her cave of extreme vanities as he called it�

�and then applying a bindi dead center in her forehead. He watched from his bed, through eyes red from sleep and smoke, while the blades of the fan circled overhead and something churned in his head. Something unruly and unpleasant.

She’d made no attempt to invite him, knowing of his antagonism to the industry. And this made him resentful, for he thought at least she could have asked. He thought she was ashamed of him—of the fact that he was not working, not earning; he didn’t have a job or a steady income like other men. That had to be it, he thought, for of late she had stopped discussing his work, too. It was as if it had ceased to matter.

It had started to pour as she left, and hearing the peep-peep of the car, she had blown him a kiss and rushed out to the “oohs” and “aahs” of her colleagues, who’d held open the door for her. In the car, she realized that he hadn’t asked her what time she’d be back or said anything about her enjoying herself. She decided she wouldn’t think about it. She’d try to enjoy herself, for she was glad to be out of the house, glad to be away from the iron grills and the giant branches that now appeared like predators waiting for her to fall.

At the mahurat the producer had gone out of his way to make her feel important. He had introduced her to famous actors, actresses, directors, and the press, saying the film wouldn’t have been possible without her. She had glowed with excitement and felt sheepish—to think this was the very world she had reviled.

Happy to be out, happy to be fussed over and appreciated, she had drunk—Jack Daniel’s with Coke, a combination that promised not to leave her with a hangover—and she had danced, a light, delirious creature unshackled after so long, drifting away from her identity of the last few months, the soul mate of a dead man walking, a dead man infecting all who came within the radius marked by him. While she did that, he drank, too, at home, pegs of vodka, first with limewater, then without, quick shots, one after the other, while the rain poured fiercely outside, and drummed against the shutters of his mind. Drummed loud and hard, in white relentless sheets.

After some time he smoked a stiff joint; then he played Machine Head by Deep Purple, swinging his arms to “Smoke on the Water” and “Highway Star,” and after that he switched to the Doors’ “The End,” and then to King Crimson’s “Epitaph,” where he mouthed the lyrics: “The fate of all mankind is in the hands of fools.” And he was sure that she was with some fool now, replete with the false graces that marked such occasions: the unctuousness, the simpering, the outstretched hands, the hugs and the kisses that went with the hype. He was sure that the world she claimed wasn’t hers was hers all the same; otherwise why would she dress like that, why so much time spent over looking good, over false appearances, the superficial things in life? And, besides, she was no longer interested in his work.

He was sure she was doing this deliberately, this planned rebellion, this meeting of people he despised. He was sure she was trying to negate him, run a cigarette over old wounds, with no one to speak up for him, no one to cry, “stop.” Oh yes, he knew all the signs of silent torture, which was why he drank more and more, and why he waited with inflamed breath, in his shorts, in his undershirt, looking like one of those street goons drunk during a festival, and which was why he’d gone out looking like that to receive her and he’d walked up to the car, the big white car with the big white hood, and, banging on it, said, “So, done your darshan to shit, paid your respects to kitsch?”

“Everything okay?” a voice from inside asked. He bent to see who this man was, who’d brought her home at 5:00 A.M., drunk and looking like she’d been screwed. He bent to see through the blinding rain, the sleek white sheets that came down and stung his neck, back, and shoulders. He peered and saw her boss, the producer, who looked angry, really angry, and she had sobbed and run inside, and he had followed, whistling.

He had thrown her out, calling her her boss’s “in-house fuck.” He said it was the right weather for a whore to be out, and he’d thrown her things out—first her records, then her mugs, then her crockery, her clothes, then her, out on the purple and silver streets, into the rain, which poured faster than her tears. She could scarcely believe that he was misunderstanding her so ruthlessly. He was tearing down everything they’d built, everything they’d cared and dreamt about.

Through blurred eyes, hair wet and swept across her face, she remembered seeing the shift of curtains, the silhouettes of faces watching from above. She remembered seeing them draw back when he’d carried out the glass center table and smashed it against the pavement. It had woken up the dogs and set them howling, and yet no one heard the screams in her heart. He’d thrown her posters after her, crushing them into a ball, and she wondered then with her Gods ruptured—his and hers—what chance did she have, what indeed?

She managed to get to Anantrao’s place in Juhu, where she spent the next few days. Anantrao was sympathetic, but like most men, he chose to keep his opinion to himself; he saw no point in getting involved. An enraged Julie wanted to speak to Nandkumar; she wanted to set him right. But Vicki extracted a promise from her that she would do nothing of the sort. Julie agreed reluctantly and, turning her ire on Anantrao, warned him not to try any such thing with her.

After a few days, Vicki called up Nandkumar, but hearing her voice, he started abusing her, demanding to know why she was screwing up his life, why she wanted to wreck his world, which was better off without her. She said she wanted to meet him just for a while; there was something important she wanted to say; after that he could decide whether to stay with her or let her go. He refused, saying he didn’t have time for another man’s whore. She winced, pleaded one more time—it wasn’t about her, wasn’t about him, it was about them and what they had created—but he did not want to listen; he simply kept abusing her, kept accusing her of things she couldn’t understand. She put down the receiver sobbing.

NOW SHE WAS ALONGSIDE THE TRAFFIC. She and the vehicles were headed the same way, to the same destination: the seaside stretch of Marine Drive. She quickened her pace and came to the horizon, which shimmered before her like some precious ore melted down. It shimmered and stretched like it was waiting to be minted into something rare, something beautiful for the twenty million residents of the city.

The traffic lined the drive bumper to bumper. Over the roofs of cars she could see the seawall; it was dotted with people who sat looking outward. The people sat and they dreamt. And the sky loomed over them, a giant tent, bright and dark in patches.

She crossed, cutting through the vehicles: buses, cars, taxis, two-wheelers, a victoria waiting patiently. She glanced at her watch. It showed seven. She’d have an hour of light to think through her plan, to decide how to do it and where—whether in the loneliness of her room or at the brink of some tall building, off its terrace. She wondered whether it should be by the rope or by the pill and whether she’d leave a note: “I, Vicki Dhanrajgiri, am doing this out of my own free will, and no one, known or otherwise, is in any way responsible for this.” She wondered whether she should add something that would get printed in the papers and onto sensitive hearts and minds. Something about life being the main culprit, about dreams being unfaithful, about hopes and expectations being the great mantraps of evolution, chutes of deceit that ended only at death’s door. No matter what she thought up, it all sounded trite and trivial. It sounded like something that had already been said, in books or in art films.

She found a spot in between a young couple and three white-haired men enjoying an animated conversation. She sat facing the traffic, not the water. Water had a way of taking you in, of making you forget the reality. It was deceptively like life itself.

Below her the ocean drummed its fury. Not hard. Not viciously. Just a playful, lapping fury that was inevitable with power and size. She thought of the tsunami that had left so many cities in disarray, which had swept away endless lives, and she wished hers, too, could have ended like that. It would have been so much easier to face that kind of fate than to be stuck with the kind of thoughts that had

assailed her in her crumbling bed-sitter of an apartment, on this day, her day of arrival, also to be, by an unpleasant coincidence, her day of exit.

Things seemed more defined now. The trick was to be out of the traffic—out of the chaos, the noise, the blare of horns, the rush of acceleration, the screech of brakes, the brinkmanship of cutting in and out, and the clever last-minute dodge to avoid hurt . . . no, none of that anymore. She smiled at the thought. Smiled because it was the only redeeming thought in an act of throwing in the towel, in an act where she still had a choice to save a life. A life that was starting in her as a seed. A life that was growing outward, more precious than her own. But which was denied a hearing, hence had no reason to be born.

Joggers slowed to catch their breath. Walkers stepped up their pace. An ice-creamwalla cycled past, ringing his bell. A chana-singwalla came and stood before some couples who were locked in conversation. He lingered, fanning the vessel that warmed the chana-sing, and he minded it not when the couples ushered him on the same way they would a beggar.

Two men came up and began feeling the trunk of a coconut tree. Both were dark and unshaven. Both wore lungis. One of them had a rope around his neck. The other had a knife tied to his waist. The men pushed at the tree and nodded to each other. Vicki looked at them curiously.

The man with the knife took the rope from the other and started to uncoil it. He loosened about four feet of it and gave the loose end to his partner. Then, strapping the rest of the coiled rope around his shoulder, he started to climb the tree. Up he went, in short, leaping froglike motions, his shoulder blades arching in and out like boomerangs. As he rose higher and higher, the rope around his shoulder unfurled, and the man below collected it.

A breeze started. The tree tilted over the road. Vicki held her breath. Would the tree snap? Would it bear the burden? What were these two up to? Her anxiety had left her now. She watched as a schoolgirl might have standing before a cage in a zoo.

Breathless in Bombay

Breathless in Bombay